CPEC in 2025: The Opaque Gamble and Pakistan’s Strategic Dilemma (Vanguard Archieves)

- Aug 22, 2025

- 3 min read

Updated: Aug 28, 2025

This article is the revised version of my earlier blog from 2017 that we posted in blogger.com. (Link to older post- https://strategicvanguard.blogspot.com/2017/03/cpec-opaque-view-from-pakistani.html )

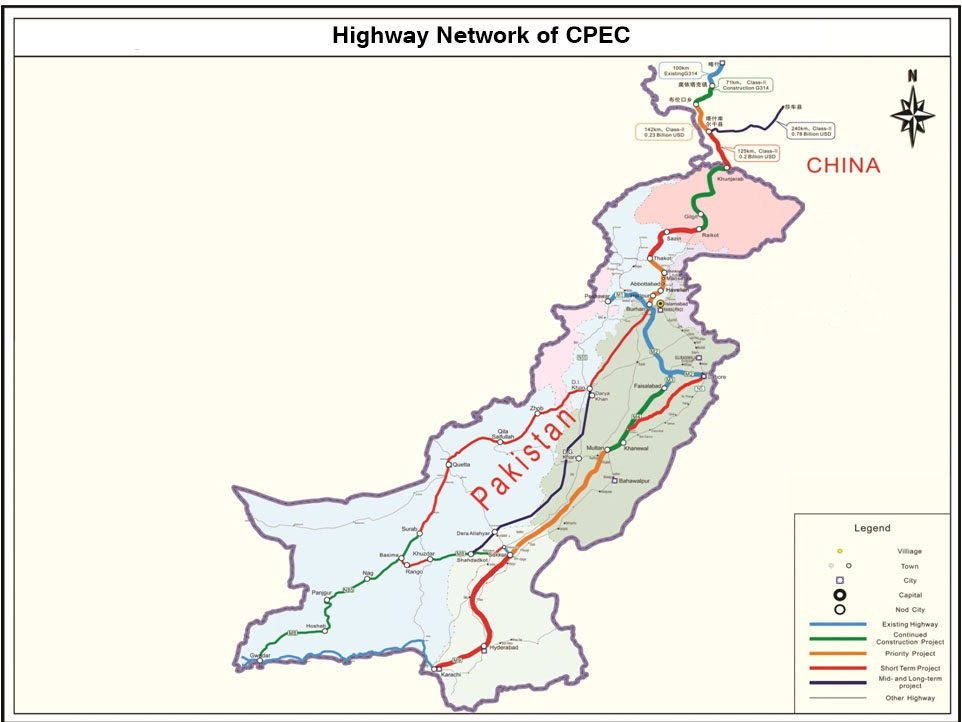

The China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), once hailed as a “game changer” for Pakistan, remains one of the most ambitious components of China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Designed to connect landlocked Western China with the Arabian Sea through Gwadar Port in Balochistan, CPEC encompasses massive investments in roads, railways, energy projects, special economic zones, and port infrastructure.

In 2017, CPEC was seen as Pakistan’s golden ticket to prosperity. Fast forward to 2025, the picture is far more complicated. While certain infrastructure projects have been completed, the economic, political, and security costs continue to raise doubts about whether Pakistan has walked into a debt trap rather than an economic miracle.

The Debt Trap Reality

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) and independent economists repeatedly warned Pakistan of the long-term risks associated with CPEC loans. Today, Pakistan’s fears have materialized.

Pakistan’s external debt has ballooned, with Chinese loans forming a significant portion.

The interest rates, often higher than international norms (ranging from 5% to even double-digit figures in some projects), have strained Islamabad’s repayment capacity.

With frequent IMF bailouts, Pakistan finds itself juggling between Beijing’s financial leverage and Washington-dominated IMF conditions—a classic geopolitical tightrope.

China’s growing control over strategic assets, including partial stakes in Gwadar Port and Karachi Stock Exchange, reflects a trend reminiscent of Sri Lanka’s Hambantota fiasco, where debt was swapped for a 99-year lease of the port.

Industrial and Trade Imbalance

Despite the rhetoric of industrial revival, Pakistan’s domestic industries have not benefitted as expected:

Chinese goods dominate Pakistani markets, often undercutting local producers.

Special Economic Zones (SEZs) remain sluggish, with limited foreign participation beyond Chinese firms.

The terms of investment remain opaque, and critics argue that Pakistan has effectively sidelined international competition in favor of Beijing’s monopoly.

This raises an uncomfortable question: What real gains does Pakistan derive if Chinese companies control the bulk of investments, profits, and trade routes?

Energy and Environmental Concerns

CPEC’s energy portfolio, once projected as Pakistan’s solution to chronic power shortages, has had unintended consequences:

A majority of projects remain coal-based, using outdated Chinese plants decommissioned at home.

Environmental costs are mounting, with air quality, water use, and climate impact worsening.

Pakistan’s renewable energy ambitions have been sidelined, leaving it locked into carbon-heavy dependency.

Security Quagmire

Security remains CPEC’s Achilles’ heel.

Pakistan created a special security division of tens of thousands of troops solely to protect Chinese workers and projects—an unprecedented move globally.

Baloch insurgents see CPEC as an extension of Islamabad’s exploitation of Balochistan’s resources, fueling attacks on Chinese nationals and infrastructure.

Islamist militant groups have also targeted CPEC-linked projects, raising Beijing’s concerns about investing in an unstable security environment.

The cost of security alone eats into the promised profitability of CPEC projects, making their long-term viability questionable.

The India Factor

India continues to oppose CPEC as it passes through Gilgit-Baltistan, territory India claims as part of Jammu & Kashmir. This legal and diplomatic challenge complicates the project’s international legitimacy.

For China, CPEC is not just about economics—it is about strategic leverage in the Indian Ocean, securing an alternative to the vulnerable Malacca Strait, and cementing its presence in South Asia.

Lessons from Hambantota – A Warning Unheeded

Sri Lanka’s experience with Hambantota Port remains the cautionary tale:

Saddled with unsustainable Chinese loans, Colombo was forced to hand over the port to Beijing on a 99-year lease.

Pakistan risks a similar fate, but with stakes far higher—CPEC’s total cost now projected at $62–65 billion, more than six times Sri Lanka’s Hambantota exposure.

Already, Pakistan has leased out parts of Gwadar Port to Chinese operators, raising fears of creeping neo-colonialism through debt dependency.

CPEC in 2025 – Success or Strategic Straitjacket?

Eight years since its hype peaked, CPEC stands at a crossroads:

Optimists argue it has given Pakistan new highways, power capacity, and the potential to become a trade hub.

Realists counter that the benefits are overstated, the debt burden is unsustainable, and Pakistan’s sovereignty is gradually being eroded.

The coming decade will determine whether CPEC becomes a launchpad for Pakistani prosperity or a Chinese straitjacket tightening around Pakistan’s economy, politics, and security.

Conclusion

For Pakistan, the CPEC gamble is both a blessing and a curse. The country desperately needs infrastructure and investment, but in handing over its economic future to China under opaque terms, it risks becoming a client state locked in debt dependency.

Unless Islamabad renegotiates terms, ensures transparency, diversifies investments by inviting global partners, and balances economic development with sovereign safeguards, CPEC may well turn into a 21st-century version of colonialism under another name.

The ghost of Hambantota looms large over Gwadar—and the future of Pakistan.

Comments